It’s not enough that we’ve filled the oceans with plastic and the atmosphere with carbon—humanity, never content with half-measures, has now managed to clutter the cosmos. Our planet’s orbit, once pristine and unblemished, is now strewn with the debris of our ambition. From defunct satellites to the occasional lost astronaut tool bag, space is becoming less of a frontier and more of a floating junkyard. And unlike on Earth, there’s no celestial sanitation department to tidy things up.

At the heart of the problem is the inconvenient fact that once you launch something into orbit, it doesn’t just politely fall back down when you’re done with it. Objects circle the Earth at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour, transforming a discarded bolt into a potentially catastrophic projectile. A fleck of paint traveling at orbital velocity can gouge a space station window. It’s like living inside a snow globe where every snowflake could puncture your lungs.

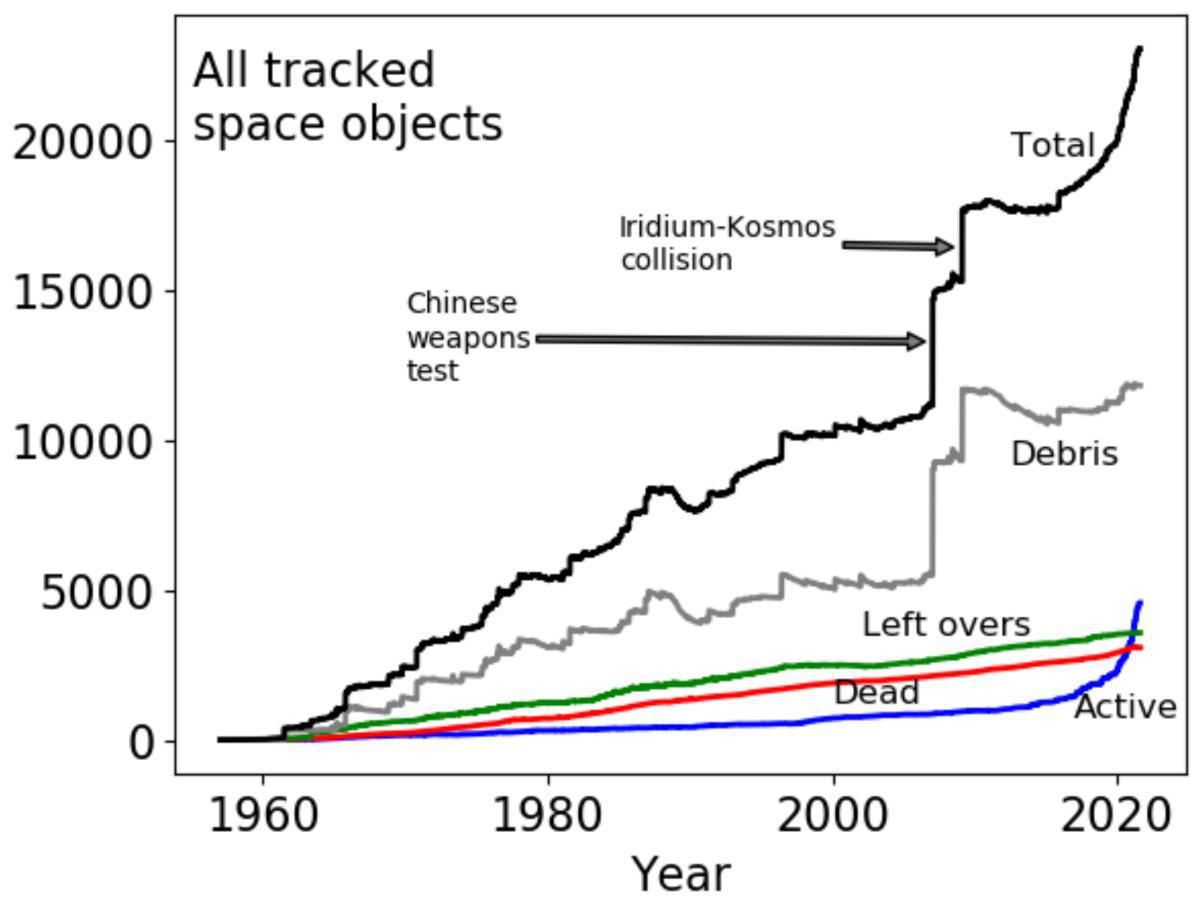

The numbers are sobering. NASA estimates that there are over 100 million pieces of debris smaller than a centimeter orbiting Earth, and about 36,000 pieces larger than a softball. While a tiny shard may seem trivial, in space it’s essentially a bullet. The International Space Station regularly has to adjust its trajectory to dodge incoming fragments—an orbital dance of survival. One collision could trigger a cascade effect, smashing satellites into ever more fragments, a scenario scientists call the Kessler Syndrome.

And the Kessler Syndrome isn’t science fiction. Imagine one satellite colliding with another, producing thousands of fragments, which then destroy more satellites, and so on. Suddenly, Earth’s orbit becomes a minefield, making future space travel prohibitively dangerous. In such a future, humanity might be trapped on its own planet—not because of rockets, but because of rubbish. It’s cosmic irony: our trash might ground us permanently.

The problem, of course, is that cleaning up space is much harder than cleaning up your kitchen. There are ideas—nets, harpoons, lasers, even giant magnets—but each faces staggering technical, political, and financial challenges. Who pays to clean up whose junk? If a piece of debris once belonged to Russia but now threatens a Japanese satellite, who gets to collect it, and under what laws? In orbit, as in geopolitics, trash is never just trash—it’s sovereignty, liability, and diplomacy.

Meanwhile, the commercial satellite boom is accelerating. Companies like SpaceX are launching megaconstellations of thousands of satellites, promising fast internet for all. Admirable, yes, but with every new satellite, the risk of collision rises. It’s the orbital equivalent of Los Angeles rush hour: everyone wants to get somewhere, and the lanes are only so wide. The race for bandwidth could inadvertently become a race toward orbital gridlock.

Authors of the study: A. Lawrence, M. L. Rawls, M. Jah, A. Boley, F. Di Vruno, S. Garrington, M. Kramer, S. Lawler, J. Lowenthal, J. McDowell, M. McCaughrean, The growth of all tracked objects in space over time (space debris and satellites), CC BY 4.0

There’s also a philosophical question lurking amid the orbital chaos: what kind of stewards are we, if we can’t keep even the emptiness of space uncluttered? Humanity often romanticizes the cosmos as the place where dreams live and futures unfold. Yet our current behavior suggests we treat it like a giant attic—out of sight, out of mind, until the ceiling caves in. This is not the mythology of noble exploration; it’s the messy reality of cosmic litterbugs.

Still, hope exists. International organizations are pushing for stricter regulations requiring satellites to de-orbit after their missions, and private companies are experimenting with debris removal tech. The European Space Agency, for instance, has funded a mission to capture and deorbit debris by 2026. It’s a small step, but perhaps the beginning of a larger orbital cleanup movement. Like all crises, the space junk problem is not insurmountable—if we can summon the will to treat it seriously.

In the end, the Space Junk Crisis is less about physics than it is about responsibility. It’s a mirror held up to humanity’s habits: our tendency to innovate before we regulate, to explore before we tidy up. If we want space to remain open for exploration, commerce, and wonder, we’ll need to learn the art of orbital housekeeping. Otherwise, the final frontier might not be infinite after all—it might just be cluttered.