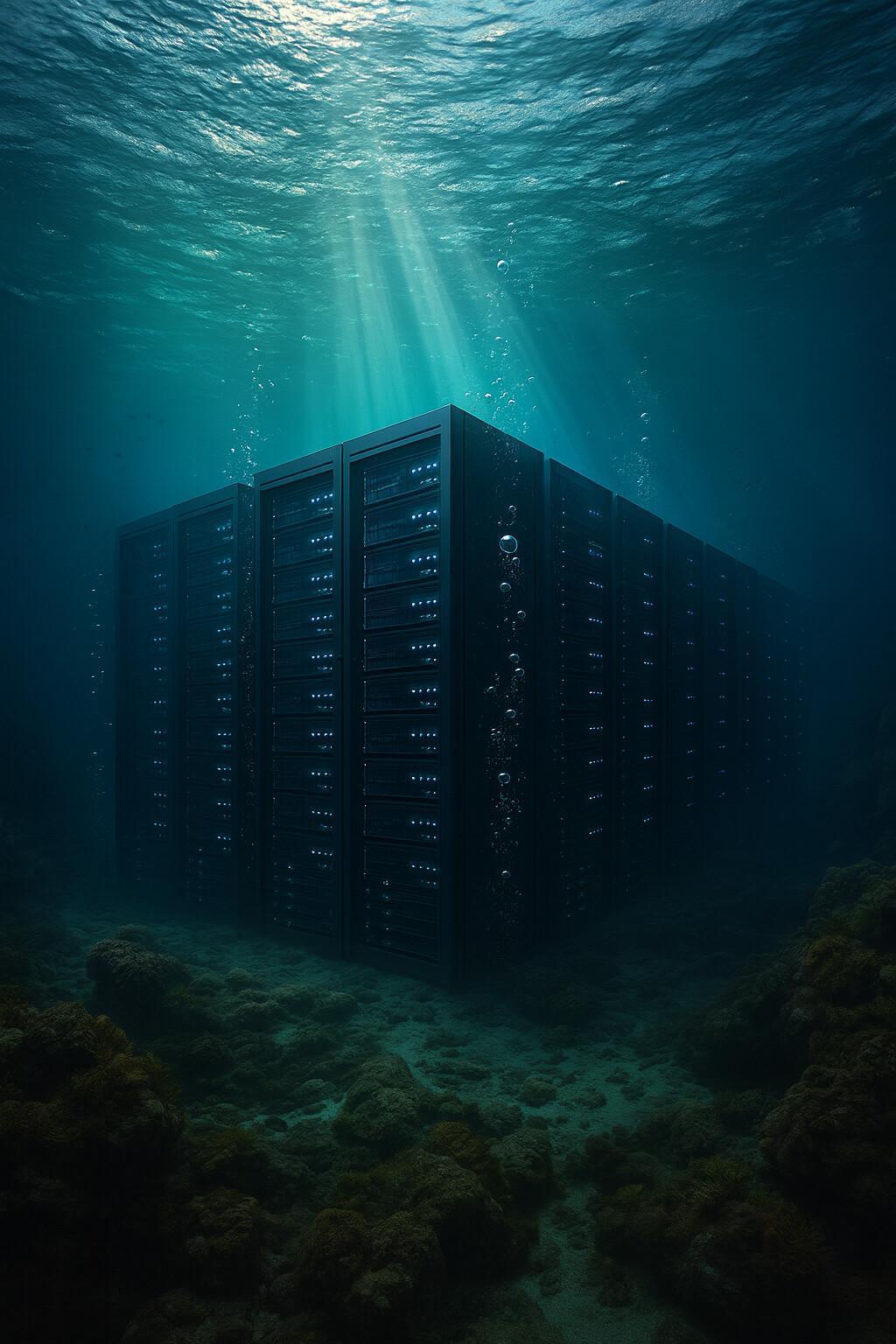

Beneath the surface of the ocean, where sunlight filters into wavering columns and the water temperature drops into a steady, cool calm, an unlikely technological revolution is quietly humming along. Underwater data centers—once a curious thought experiment—are emerging as a serious contender in the race to meet humanity’s ever-growing appetite for cloud computing. Imagine the humming racks of servers you might find in a desert warehouse instead placed inside a pressure-proof cylinder, sunk to the seafloor, surrounded by fish, kelp, and the constant embrace of the sea. This is not science fiction—it’s Microsoft’s Project Natick, and similar initiatives, proving that the deep blue might just be the future of the internet.

The concept springs from a simple, if slightly audacious, insight: data centers get hot, and water is good at cooling things down. Traditional land-based data centers spend enormous amounts of energy on cooling systems—air conditioning for machines rather than people—sometimes accounting for up to 40% of their total energy consumption. By placing servers underwater, engineers can harness the naturally low and stable temperatures of the ocean, reducing the need for power-hungry cooling systems and, in theory, slashing operational costs. In a world increasingly conscious of climate impact, that’s an enticing proposition.

The logistical challenges, of course, are immense. These submerged data centers must be housed in watertight, corrosion-resistant containers designed to withstand pressure, biofouling (that charming tendency of marine organisms to colonize anything stationary), and the occasional curious shark. Once deployed, maintenance becomes an all-or-nothing proposition: these are not facilities that technicians can casually walk into. Instead, they are sealed units expected to run autonomously for years before being retrieved for upgrades or repairs. In Microsoft’s tests, servers ran for two years underwater without a single mechanical failure, a striking improvement over their land-based cousins.

Part of this unexpected reliability comes from the sealed, controlled environment. Traditional data centers are filled with dust, human error, and fluctuating temperatures; underwater, none of these are factors. The servers are left alone in a nitrogen-filled chamber, operating without the disturbances that plague their terrestrial counterparts. In a strange way, these oceanic machines lead a monastic existence—cut off from the world, dedicated solely to processing and storing humanity’s endless stream of data.

There’s also a geographic advantage to consider. Much of the world’s population lives near coastlines, so placing data centers offshore can dramatically reduce the physical distance between servers and end-users. In the language of the internet, this reduces latency—the tiny but crucial delays in transmitting data—making web services faster and more responsive. For companies streaming video, hosting multiplayer games, or managing financial transactions, shaving milliseconds off response times can be a competitive edge.

Environmentalists, though, remain cautious. While proponents argue that underwater data centers could run entirely on renewable energy—tapping into offshore wind, tidal, or wave power—the ecological impact of placing metal cylinders on the seabed remains under-researched. Will the constant heat output attract certain marine life while driving away others? Could electromagnetic interference affect sensitive underwater ecosystems? Early tests suggest minimal disruption, but scaling from prototype to global infrastructure is a leap fraught with unknowns.

The economic implications are equally intriguing. Deploying underwater data centers is expensive, especially during the experimental phase, but proponents argue that long-term savings in cooling and land costs will make the model competitive. Land in urban areas is costly, and the environmental permitting process for large new server farms can be contentious. By sinking their operations offshore, companies might bypass some of these political and real estate hurdles—though maritime regulations present a different labyrinth to navigate.

There is also a certain poetic irony in storing the most ephemeral of modern commodities—data—in one of the most ancient, unyielding environments on Earth. Our cat videos, spreadsheets, and virtual reality worlds could, in the near future, live deep beneath the waves, guarded by layers of steel, saltwater, and perhaps a passing school of fish. The juxtaposition feels both futuristic and primal, a reminder that even our most advanced technologies are still bound by the laws of physics and the limits of nature.

If the trend continues, we might see coastal “server harbors” where modular underwater data centers can be swapped in and out like cargo containers, running off the grid with renewable ocean energy. The ocean floor could become not just a site of natural wonder but a cornerstone of the digital economy. Underwater data centers might even serve dual purposes, doubling as scientific monitoring stations to track marine environments in real time, turning infrastructure into a tool for both commerce and conservation.

For now, the field is still experimental, but the trajectory is clear. The internet is no longer just in the cloud—it’s in the currents. Whether these submerged vaults of computation become a niche solution or a dominant architecture will depend on engineering ingenuity, environmental stewardship, and, inevitably, economics. One thing is certain: in the future, when you stream a movie or send a message, part of that digital journey might pass through a silent, glowing capsule resting on the ocean floor.