When we talk about DNA, names like James Watson and Francis Crick typically get all the spotlight—and occasionally a Nobel Prize. But in the shadow of the double helix stands Rosalind Franklin, whose X-ray crystallography work provided the crucial photographic evidence that made their model possible. Franklin wasn’t just the woman with the microscope; she was the scientist who literally illuminated the shape of life. Yet for decades, she was relegated to a scientific footnote—until historians, feminists, and frankly, people with eyes, decided to take a second look.

Born in 1920 into a well-to-do British family, Franklin was brilliant from the start and determined to pursue science at a time when laboratories were still something of a gentleman’s club. She studied physical chemistry at Cambridge and later honed her expertise in X-ray diffraction in Paris—a technique that sounds like sci-fi but basically means bombarding crystals with X-rays and interpreting the scattered light like some sort of molecular tarot. Her precision, rigor, and stubborn attention to detail made her both respected and, let’s be honest, feared.

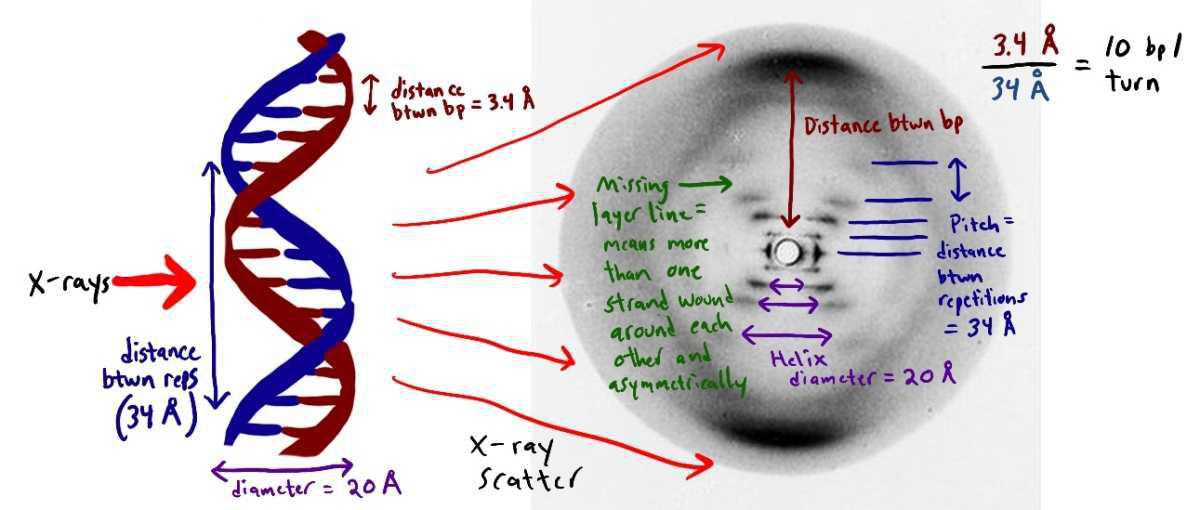

Franklin’s most famous contribution came during her time at King’s College London, where she was tasked with figuring out the structure of DNA. Photograph 51—an X-ray diffraction image of DNA that she captured—revealed its helical form with eerie clarity. Unfortunately, this image was shown to Watson and Crick without her knowledge or consent. It gave them the final piece they needed to build their now-famous model. If DNA was the code of life, Franklin was the cryptographer—just one whose cipher was shared behind her back.

The ethical question here isn’t whether Watson and Crick were clever—they were—but whether scientific discovery should be a relay race or a heist. Franklin didn’t get credit during her lifetime, partly because she died in 1958 of ovarian cancer, aged just 37, and partly because history loves a tidy narrative starring men with messy hair and eureka moments. The Nobel Prize committee doesn’t award posthumous honors, so Franklin’s name was never added to the 1962 Nobel awarded to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins. Timing, it seems, is everything—even in science.

But to define Franklin solely by the Nobel she didn’t win would be to misunderstand her legacy. She was not a victim so much as a vanguard. She went on, in her short career, to do pioneering work on the molecular structures of viruses, including the tobacco mosaic virus and the polio virus, laying foundations for structural virology. Her notebooks are meticulous, her photographs still legendary, and her scientific skepticism—she was critical of premature models—profoundly modern.

Franklin also complicates the “wronged woman” trope. She wasn’t ignored because she was meek—she was formidable, sarcastic, and scientifically uncompromising. She didn’t want to be a heroine of feminism; she wanted to be a damn good scientist. Her tragedy, if it can be called that, lies not in how she saw herself but in how the world preferred to see her: as a supporting actress in a drama where she wrote half the script.

In recent years, the cultural tide has turned. Books like Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA and television portrayals have resurrected her reputation, casting her not just as a genius obscured, but as a symbol of how institutional biases distort the history of ideas. Statues have gone up, stamps have been issued, and maybe—just maybe—a few more high school textbooks are getting it right. At long last, the crystallographer is coming into focus.

Franklin’s story reminds us that science isn’t just about data—it’s about power, politics, and the people who get remembered. In a world still arguing about who gets credit and why, she’s the unsung lyric in the song of modern biology. And like the double helix she helped reveal, her legacy spirals on, elegant and enduring.