We tend to think of play as something we grow out of, an activity confined to sandboxes, stuffed animals, and recess. But the impulse to play doesn't disappear with age; it just camouflages itself in adult disguises. The very impulse that led us to create worlds with blocks evolves into decorating homes, trying on identities in digital worlds, or getting lost in fantasy novels and weekend hobbies. Beneath the veneer of adulthood, the human imagination never stops asking the same question it did in childhood: What if?

Psychologists have long argued that play isn't just a frivolous pastime—it's an essential part of cognitive and emotional development. But its role doesn't end there: For adults, it becomes a form of cognitive flexibility, a way of experimenting with the possible without real-world consequences. Whether a novelist slips into the mind of a character or a gamer inhabits a digital avatar, they're doing more than escaping reality—they're rehearsing alternative selves, expanding the range of what it means to be human.

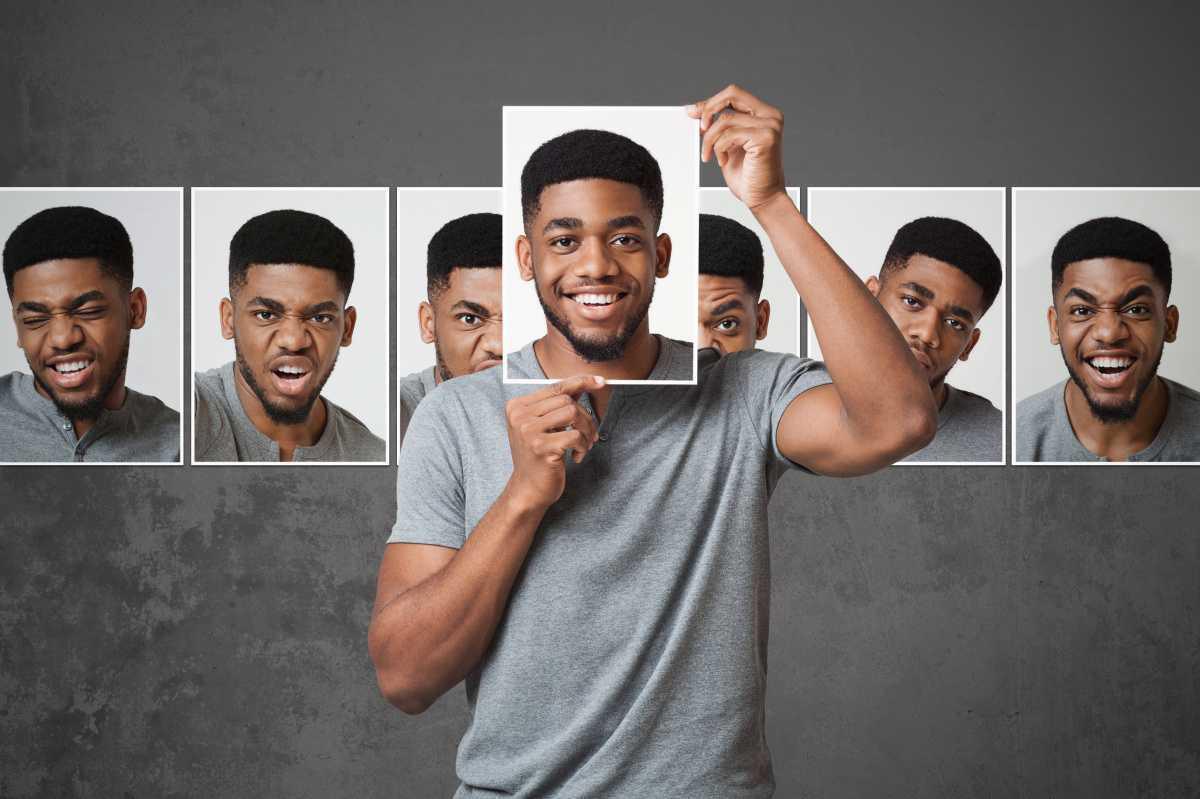

Pretending, in this light, is not immaturity—it's rehearsal. We act "as if" not because we're deluded, but because imagination gives us tools reality can't. Pretending to be brave helps us act bravely; pretending to belong helps us learn how to. In social life, this play instinct smooths the edges of anxiety and performance. We "play" professional, "play" charming, "play" confident-not as deception, but as a kind of hopeful simulation, one that allows growth through mimicry. Adults may call it "practice" or "presentation," but the psychology is the same as a child's tea party.

Even our rituals of leisure-sports, theater, fashion, and social media are grown-up playgrounds where identity and fantasy mingle. A soccer match is just pretend warfare. A fashion runway, a collective act of make-believe about elegance and status. Online, we curate and costume our personas in ways that reveal the enduring pleasure of role-play. The platforms may be digital, but the impulse is prehistoric: to create, perform, and test our place in the tribe through shared imagination.

The modern world, paradoxically, needs this kind of play more than ever. In this age obsessed with productivity and authenticity, we risk losing that creative elasticity. Adults who never play become brittle—too literal, too linear, too afraid of the absurd. Pretending keeps the psyche supple; makes us resilient enough to imagine alternatives when reality becomes unbearable or too narrow to contain us. A society that forgets how to play forgets how to innovate.

Philosophers like Schiller and Huizinga saw play as the foundation of culture itself. According to Schiller, humans are fully human only when they play—because play unites reason and emotion, order and freedom. Huizinga’s Homo Ludens argued that law, art, and even war evolved from playful contests. Through play, societies experiment with moral boundaries and aesthetic ideals without total collapse. To play, then, is not to flee reality—it’s to rehearse civilization itself.

Even creativity in adulthood—whether in art, science, or entrepreneurship—requires this same instinct. "Imagination is more important than knowledge," Einstein famously said. What he meant was not childish whimsy but the courage to think in innovative ways—to manipulate the laws of reality in one's mind until something new emerges. Every invention begins as a form of pretend: someone imagines a world that doesn't yet exist and asks, Why not?

To play is to heal. In therapy, role-play and imaginative visualization allow people to reframe trauma and regain agency. By pretending differently, we rewrite the scripts we once felt trapped inside. The quiet rebellion against despair can also be done casually through daydreaming. Pretend long enough that peace or beauty or courage is possible, and the mind begins to carve out a space where it is.

So maybe the true mark of maturity isn't abandoning play but refining it-turning childish fantasy into creative empathy, performative mastery, and imaginative resilience. We may no longer build castles out of sand, but we still build them in words, ideas, and dreams. The adult who can still pretend is not stuck in childhood; they are fluent in possibility. For in the end, play is not a refusal to grow up—t's how we continue to grow.