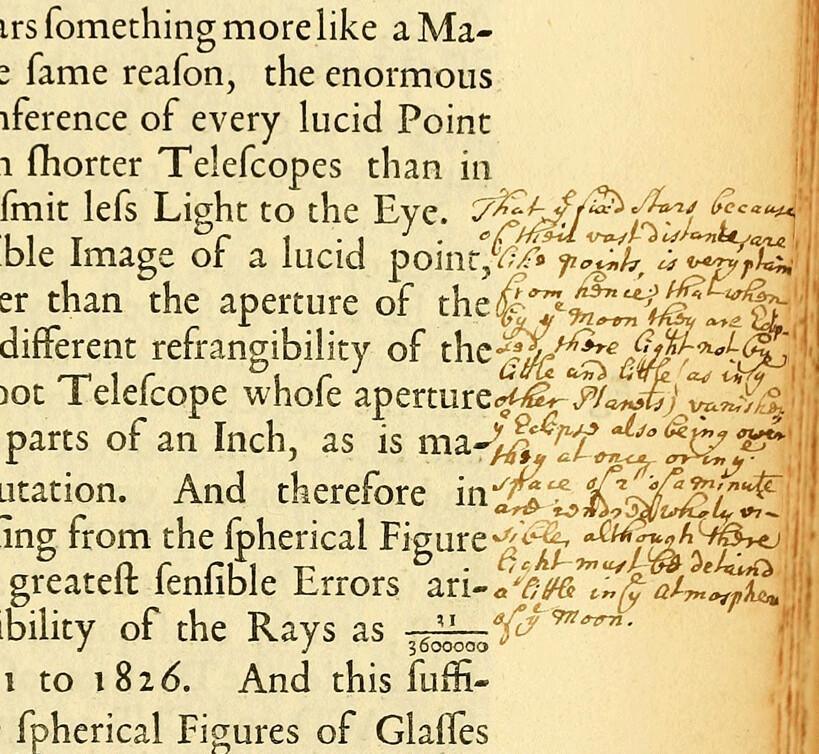

Once upon a time, books were not pristine objects meant to be displayed in untouched perfection. They were living, breathing companions. Readers scrawled notes, circled phrases, drew arrows, and sometimes even argued with the author in the margins. These handwritten interventions—known as marginalia—were more than annotations; they were dialogues across time. A book without marks was incomplete, like a conversation that never left the throat.

Today, however, the practice has become endangered. In an era of e-books, audiobooks, and digital annotation tools, handwriting in the margins has receded to the edges of memory. Instead, we highlight with a finger-swipe, bookmark with a tap, or rely on search bars to recall a phrase. Efficiency has replaced intimacy. The margins—once a site of whispered rebellion, revelation, or humor—are eerily silent.

Marginalia was never merely practical. It was an art form, one that allowed readers to perform an act of co-authorship. Take Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who was notorious for his scrawled commentaries in nearly every book he touched. His notes have since become as studied as his poems. Vladimir Nabokov’s butterflies, sketches, and obsessive underlines reveal not just his tastes but his neuroses. Marginalia transforms the solitary act of reading into a layered text, one in which past and present readers converse across the page.

The practice also carried a democratic energy. A student annotating Shakespeare in a dog-eared paperback could enter the same literary conversation as a scholar. A casual reader’s “yes!” or “nonsense!” beside a passage could echo the more formal critiques of academia. Marginalia was a way of collapsing hierarchies: the book belonged not only to the author but to everyone who wrestled with it. The margin was a tiny republic of thought.

Of course, not all marks were profound. Some were charmingly mundane: grocery lists tucked into the corners of theology texts, doodles of flowers alongside Aristotle, recipes scribbled in the back of novels. But these too were valuable. They made books personal artifacts, objects infused with the texture of a life. A library was not just an archive of texts but a community of human presences layered into its pages.

The decline of marginalia mirrors a broader cultural shift. We are pressured to consume quickly, efficiently, without lingering. Speed-reading apps, algorithmic recommendations, and the endless scroll of feeds leave little room for slow, dialogic engagement. To write in the margins requires patience. It requires the reader to risk slowing down, to claim a book as one’s own. This act feels increasingly radical in a world where digital platforms quietly insist that ownership is an illusion and every book is borrowed from the cloud.

Yet marginalia survives in pockets of resistance. Used bookstores remain treasure troves, their shelves filled with ghostly traces of former readers. One may find a love note on the flyleaf of a textbook, or a biting critique scrawled in a philosophy tome: “Wrong! Too reductive!” Some scholars now deliberately study these annotations, treating them as windows into reading practices of the past. They are archaeological fragments of intellectual history.

Digital technology, ironically, has both eroded and revived marginalia. Annotation platforms allow readers to highlight and comment collectively on online texts, turning the margin into a public forum. Social media screenshots of annotated pages circulate like artifacts of intimacy. But there is something irreplaceable about ink on paper—the feel of graphite pressed into the grain, the peculiar slant of handwriting, the accidental coffee ring sealing a thought. Digital marginalia may capture function, but not the soul.

Reviving the art of marginalia might be less about nostalgia and more about reclaiming a form of intellectual ownership. To annotate is to insist: I was here, I thought, I argued, I agreed. It transforms reading from passive reception into active creation. In a world where so much content passes over us like waves, writing in the margins is an anchor—a record that we engaged rather than drifted.

Perhaps the best argument for marginalia is its unexpected afterlife. An annotated book carries two stories: the printed one and the lived one. To stumble upon a stranger’s notes is to meet an anonymous companion, someone who walked the same path and left markers behind. A margin becomes a space of communion, fragile but enduring. In that sense, marginalia is not lost—it only waits for readers bold enough to reclaim it.

To write in the margins is to resist invisibility. It is to speak back to power, to beauty, to knowledge. It is to say: I am not just consuming this text, I am conversing with it. In reviving marginalia, we might rediscover the joy of reading not as transaction but as relationship—messy, personal, and gloriously alive.