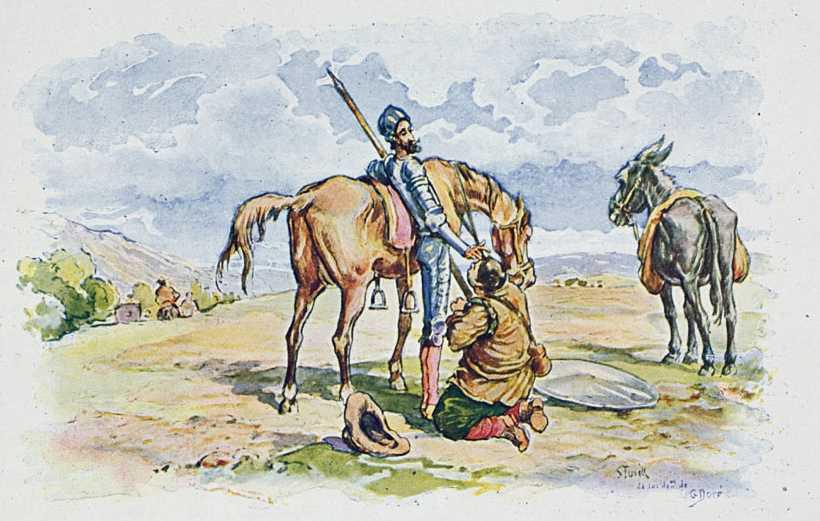

Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, first published in two parts (1605 and 1615), is often considered the first modern novel. Written in Spain during the waning years of the Golden Age, it follows the misadventures of Alonso Quixano, a middle-aged man who, after reading too many chivalric romances, reinvents himself as the knight-errant Don Quixote de la Mancha. Armed with outdated armor, a scrawny horse named Rocinante, and an unfailing belief in knightly ideals, he sets off to right wrongs and protect the helpless. His faithful squire, Sancho Panza, serves as both his comic foil and his tether to reality.

The genius of Don Quixote lies in its dual nature: it is simultaneously a parody of medieval romances and a meditation on reality, illusion, and human aspiration. Cervantes lampoons the absurdity of knights charging at giants and rescuing maidens, but in Don Quixote’s delusions he finds something deeply moving. The “knight of the sorrowful face” mistakes windmills for giants and inns for castles, but he also insists on seeing the world not as it is, but as it ought to be. This tension between madness and vision is at the core of the novel’s enduring appeal.

Sancho Panza, though initially driven by promises of wealth and land, becomes an unlikely partner in Quixote’s dream. His earthy pragmatism contrasts with his master’s lofty ideals, yet Sancho himself begins to believe, if only in part, in the nobility of Quixote’s vision. Their relationship evolves into one of literature’s most memorable friendships—a balance of folly and wisdom, mockery and loyalty. Through Sancho, Cervantes gives voice to the ordinary man, skeptical yet susceptible to hope.

Beyond its characters, the novel is remarkable for its layered storytelling. Cervantes frames the narrative as a translation of a historical chronicle by an invented Moorish historian, Cide Hamete Benengeli. This self-referential playfulness anticipates modern metafiction, blurring the lines between fiction and reality. Readers are constantly reminded that the story they are consuming is a constructed one, destabilizing the boundary between truth and imagination.

The novel also reflects Spain’s shifting social and cultural landscape. By Cervantes’ time, the age of knights and noble quests was long gone, replaced by bureaucratic empire and economic hardship. Don Quixote’s insistence on reviving knight-errantry becomes an allegory for nostalgia, a longing for ideals that no longer fit the present. In this sense, the book is not just comic but tragic, a story of someone too late for his own time.

Despite its satire, Cervantes imbues Don Quixote with dignity. The knight’s madness is also his greatness: he insists on a higher vision of justice, honor, and beauty in a world often marked by cruelty and banality. Readers laugh at his follies, but they also admire his unshakable determination to believe in something better. Cervantes suggests that sometimes illusions, however impractical, are what keep people human.

The second part of the novel, published a decade later, deepens this exploration. Don Quixote and Sancho are now famous within the story itself, and other characters manipulate them for amusement. This reflects Cervantes’ awareness of his own readers, who, by that time, had embraced the duo as cultural icons. The characters become conscious of their literary status, creating one of the earliest examples of self-aware fiction.

Literary critics often describe Don Quixote as a work that inaugurates the modern novel precisely because of its psychological depth, self-reflection, and social commentary. Unlike earlier romances that idealized heroes, Cervantes gave readers flawed, contradictory, yet profoundly human characters. In doing so, he set the stage for later novelists like Dickens, Flaubert, and Dostoevsky, who would continue to explore the complexity of human consciousness.

Over the centuries, Don Quixote has become more than just a character—he is a symbol. For some, he embodies noble idealism in a cynical world; for others, he represents folly, delusion, and wasted effort. His tilting at windmills has entered common speech as shorthand for fighting imaginary battles. But his refusal to abandon his dream, even in the face of ridicule, also makes him a model of persistence and faith in the human spirit.

In the end, Don Quixote dies disillusioned, having renounced his knightly persona and returned to reality as Alonso Quixano. Yet his story transcends that final defeat. Cervantes leaves readers with the paradox that perhaps it is madness to live without ideals, and sanity itself may be a kind of surrender. The novel remains a testament to the power of imagination, a work that continues to shape literature and inspire readers more than four centuries after its publication.