Book covers, those glossy or matte shields guarding the first page, are rarely neutral. They are miniature billboards, cultural messengers, and subtle propagandists, each one quietly lobbying for a reader’s attention. The politics of book covers lie in their ability to shape how we interpret a text before even opening it—an interplay of marketing, design, and ideology. They sell not just stories, but entire identities, lifestyles, and beliefs. A book cover is as much a product of its cultural moment as it is of its author’s vision, though often the author’s control is the weakest influence in the room.

Publishers have long known that a cover can dictate a book’s reception. In commercial genres—romance, fantasy, thriller—the design cues are almost codified: pink cursive fonts promise love, shadowy alleyways promise danger, maps or dragons promise an epic journey. These are not arbitrary; they signal to both the market and the reader who this book is “for.” But therein lies the politics: such visual shorthand reinforces genre boundaries and audience segmentation, effectively gatekeeping who feels welcome to pick up the book. The wrong cover can alienate potential readers just as easily as it can entice them.

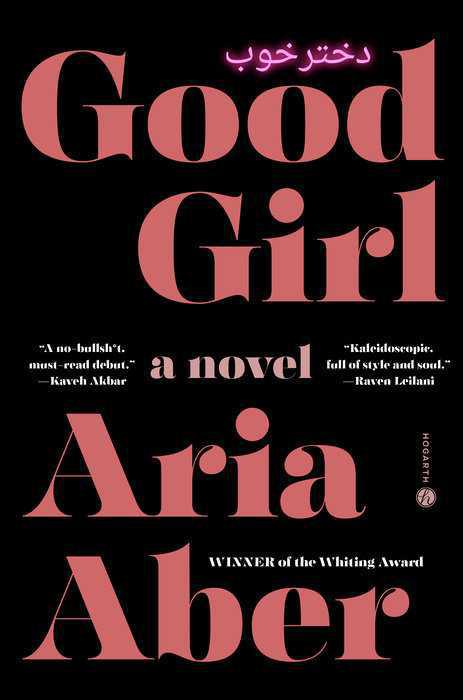

Consider the issue of “whitewashing” in cover design. Numerous books by authors of color have had their protagonists—described in-text with specific ethnic or racial identities—depicted as lighter-skinned or even entirely white on the cover. This practice, justified by marketing departments as “broadening appeal,” erases marginalized identities and perpetuates systemic bias in publishing. It sends a clear message: diversity might be celebrated in theory, but only if it’s palatable to a presumed white majority audience. The cover becomes an ideological filter, muting narratives that were meant to be bold.

Gender politics play out in equally insidious ways. Books written by women, particularly in literary fiction, often face “cover sexism”—a tendency to package their works in pastel palettes, whimsical illustrations, or “soft” imagery, regardless of the book’s actual tone or subject matter. Serious novels by men are granted minimalist, authoritative covers; serious novels by women are often given florals. The implicit message is that women’s writing is domestic, romantic, or “light,” and therefore less universal. It shapes not only who reads the book, but how it’s critically received.

© Vyacheslav Argenberg / https://www.vascoplanet.com/, Modern art, Book covers 2, Rostov-on-Don, Russia, CC BY 4.0

Even typography can be politically loaded. The choice between serif and sans-serif fonts, bold capitals or delicate script, is never entirely aesthetic. Certain typefaces evoke authority, rebellion, nostalgia, or futurism, and these associations are embedded in cultural hierarchies. A memoir by an activist printed in the typography of a luxury brand sends a different message than the same text set in bold protest-style lettering. Designers make these choices under the influence of trends, market data, and the subtle pressure to position a book within the hierarchy of “serious literature” versus “popular entertainment.”

Then there’s the question of global publishing. The same book can have radically different covers in different countries—sometimes to suit local tastes, sometimes to meet political restrictions. A cover in one market may emphasize romance, while another might foreground political rebellion. In authoritarian states, certain imagery might be banned outright, leading to covert symbolism or abstract design that slips past censors. In this sense, book covers become sites of negotiation between artistic expression, political climate, and the safety of the author and publisher.

The digital era has added new layers to this politics. Online marketplaces like Amazon reduce covers to thumbnail size, pressuring designers to make imagery bolder, simpler, and instantly legible. This shift favors certain aesthetic styles and disadvantages books whose appeal lies in subtlety or intricate design. Social media, especially “BookTok” and “Bookstagram,” has also influenced covers, rewarding books that look photogenic in flat-lays or videos. In essence, a book now has to be as camera-ready as it is reader-ready.

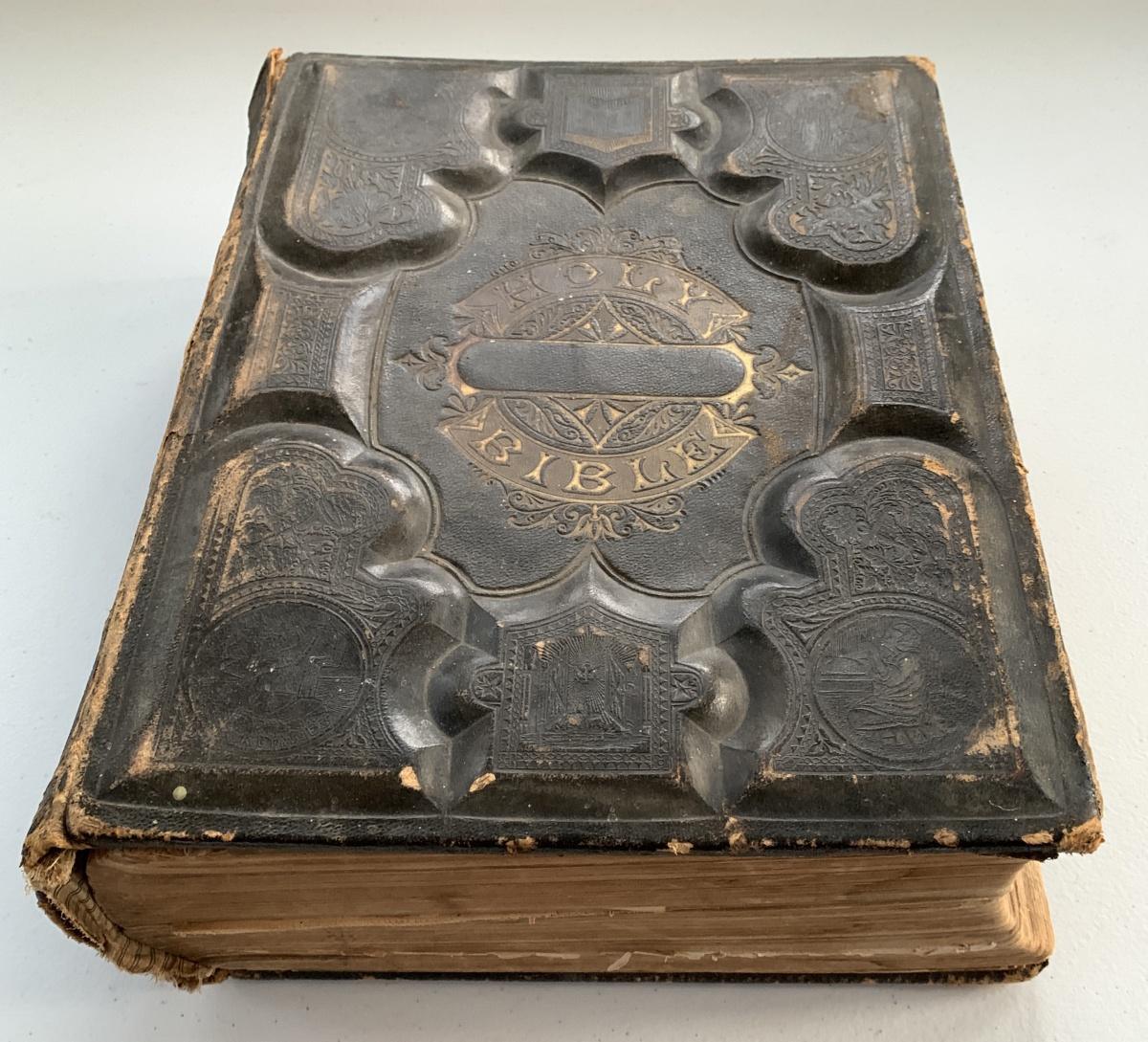

John P Salvatore, Holy Bible The Improved Domestic Bible London Schuyler Smith & Co 1880 Maps, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ironically, covers can also be weaponized in acts of literary rebellion. Independent and small press publishers sometimes intentionally reject the glossy conventions of mainstream publishing, producing covers that are rough, minimalist, or deliberately provocative. These covers signal their resistance to corporate homogenization, challenging the idea that marketability should dictate a book’s visual identity. Of course, this too becomes a kind of branding—rebellion as an aesthetic, often marketed to niche but loyal audiences.

For readers, the politics of book covers are both invisible and omnipresent. Most people don’t consciously think about the choices that go into a cover, yet these choices shape expectations, reinforce stereotypes, and influence purchasing behavior. The cover can act as an unspoken contract: “This is the kind of story you are buying, the kind of person you’ll be if you read it.” It’s a seductive promise, and a dangerous one, because it often narrows rather than expands the possibilities of interpretation.

In the end, a book cover is less a frame and more a mirror—reflecting not just the content inside, but the cultural and economic forces surrounding it. Every color, font, and image is part of a negotiation between art and commerce, identity and marketability, visibility and erasure. The politics of book covers reveal that, before we ever turn the first page, we’ve already been told how to read the book. Whether we accept that framing—or challenge it—becomes part of the reading act itself.