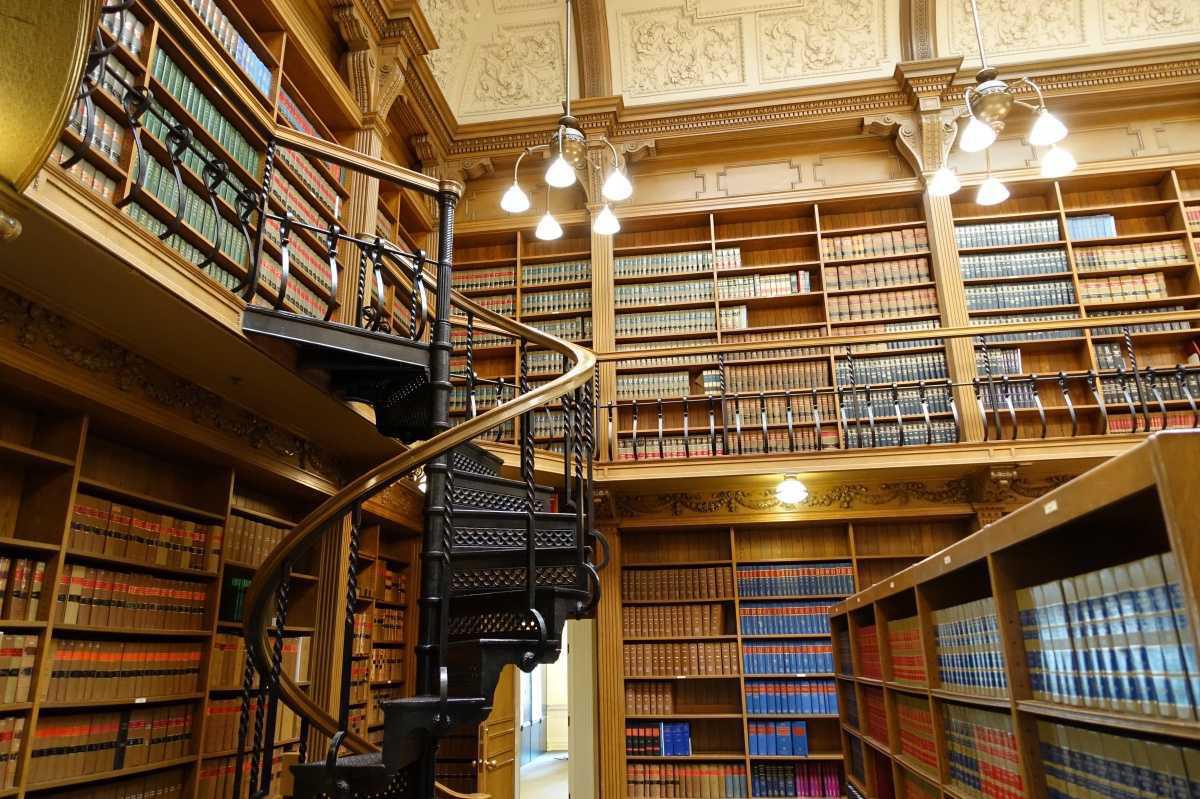

rdsmith4, Great Books, CC BY-SA 2.0

Some books don’t just stand the test of time—they define it. Known collectively as The Great Books, these works form a curated canon of literature, philosophy, history, and science that have profoundly shaped Western thought. The list varies depending on who’s curating, but names like Plato, Shakespeare, Dante, and Darwin usually make the cut. Whether inscribed on library walls or debated in college seminars, the Great Books continue to spark conversations about what it means to be human, how we ought to live, and what constitutes truth.

The idea of the Great Books as a formal collection was popularized in the mid-20th century, particularly through the work of Mortimer Adler and Robert Hutchins, who spearheaded the Great Books of the Western World series published by Encyclopædia Britannica in 1952. Their goal wasn’t just to make these texts accessible, but to promote what they called the “Great Conversation”—a chain of dialogue across centuries where each book responds to those that came before. In their view, education wasn’t about memorizing facts but joining that timeless conversation.

The Great Books range in genre and era, from Homer’s The Iliad to Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. You’ll find medieval theology beside Enlightenment politics, and Greek tragedies alongside modern novels. What ties them together isn’t just influence, but the depth with which they probe fundamental questions—justice, love, beauty, mortality, power, and the divine. These texts don’t offer easy answers; they’re designed to make readers wrestle with ambiguity, nuance, and contradiction.

Of course, the list isn’t without controversy. Critics argue that the canon reflects a narrow slice of human history—mostly male, mostly European, and mostly elite. Why should Plato count as “great,” but not Confucius? Where are the voices of women, indigenous thinkers, and the non-Western world? These critiques have led to expanded reading lists in modern classrooms, but they’ve also deepened the conversation about what we value, and why. The Great Books aren't a finished list—they're a starting point for debate.

Interestingly, many Great Books weren’t considered “great” in their time. Some were banned, ridiculed, or forgotten for centuries before being rediscovered. Melville’s Moby-Dick flopped when first published. Galileo’s scientific writings got him excommunicated. Even Socrates, the patron saint of philosophy, was executed for corrupting youth. Their eventual canonization is as much a reflection of cultural shifts as literary merit, reminding us that greatness often arrives posthumously and controversially.

Reading the Great Books today can feel like time travel. You enter the minds of people who lived thousands of years ago—and yet, their questions still sound uncannily familiar. How should society be organized? What makes a life meaningful? Can we ever truly know anything? If these questions remain unresolved, perhaps it’s because the answers aren’t fixed—they evolve with us. The Great Books don’t give conclusions; they give tools to think more deeply.

Educational programs built around the Great Books, like those at St. John’s College or the University of Chicago, emphasize dialogue over lecture. Students don’t memorize what Aristotle thought—they argue with him. This method encourages critical thinking, civil discourse, and intellectual humility. You don’t read these books to agree with them; you read them to sharpen your mind against them, like a blade on a whetstone.

In the end, the Great Books are less about reverence than relevance. They persist not because they’re old, but because they’re alive. Whether you approach them as sacred texts, cultural artifacts, or intellectual battlegrounds, they offer something rare in today’s noisy world: sustained attention to complexity. That’s why we still read them—not to worship the past, but to better understand the present.